The Citadel spirit lives on, all in the Memorial Day family

They are on the minds of our Charleston family this Memorial Day and in my mind on all days. But to help the younger ones understand, the complete story of our family’s heroes, as known from many old newspaper and military articles, is now written in one place for them to keep and to pass on.

When my father, Gen. Davis, first entered the army prior to World War II, he was a young officer and fortunate to be a member of the honor guard at Arlington National Cemetery.

In the darkness he would ride his horse to inspect the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier — on guard 24 hours a day, riding past the thousands of head stones and heroes buried there from America’s past wars. The only noise was the sound of the horse’s hooves. As Gen. Davis rode through the yard, he sensed the spiritual presence of all those great heroes buried there, relying on him to watch over the cemetery.

Years later, after unimaginable horrors experienced by fighting the Nazis across Europe with the Third Armored Division in World War II, he was haunted by experiences such as liberating concentration camps, or surviving the misery of the Battle of The Bulge.

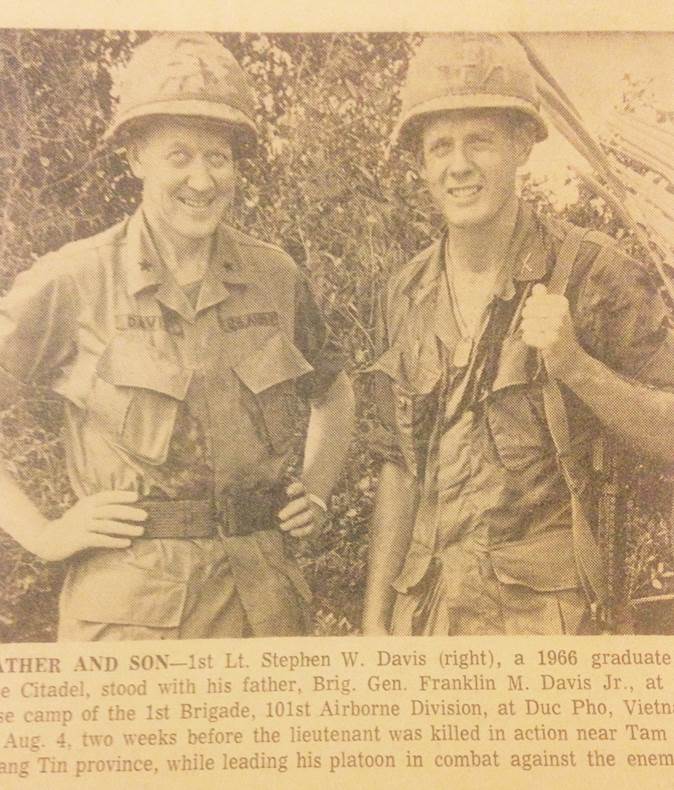

Next, it was Vietnam, long before the public conflict, and as a general, administering what we all later learned was a secret war against the North Vietnamese in Laos and Cambodia. In 1967 Gen. Davis’ oldest son, Stephen, a member of The Citadel Class of 1966, joined him. Father and son were at a remote 101st Airborne Division base camp in the jungles. Just a week later, Lt. Davis and his platoon found what the U.S. forces had been looking for: the 21st North Vietnamese Regiment (NVA) in full uniform, with headquarters buried in a mountain deep inside South Vietnam. An Associated Press news reporter was following Lt. Davis and was there when he was killed in combat shortly after attacking the NVA facility. The story of the death of Lt. Davis, my older brother, hit the pages of most American newspapers, including the then News and Courier; he was the son of a well-known general, after all.

The headlines read, “General’s son dies a hero.” Against overwhelming odds, in the surprise NVA ambush, Lt. Davis fought to the bitter end. He called in artillery to assist in the attack on the well-entrenched North Vietnamese regiment. Wounded, he ordered the others in his unit to get out while he stayed behind, continuing to engage the enemy any way he could.

Many years later, a surviving soldier who fought beside Lt. Davis that fateful day said, “He saved a lot of Americans. He covered us so we could escape the tremendous onslaught. Blinded by his injury, Lt. Davis kept fighting and stayed on the radio, raining artillery on the enemy.”

A soldier with the recovery unit that arrived the next day, also a graduate of The Citadel, commented that in his two tours in Vietnam, he had “never seen so many dead North Vietnamese enemy soldiers on one mountainside.” Lt. Davis was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, the nation’s third highest medal for heroism. According to those who moved on from the battle, the 101st Airborne Division was not able to catch up with NVA again in the open for a year, and then decimated it with B52 carpet-bombings.

It remains difficult to even imagine the emotions of our father. Gen. Davis accompanied the flag-draped coffin of his 23-year-old son halfway around the world, back to America.

The military funeral at Arlington National Cemetery, which had been fueled by the news reports and the country’s desire to honor heroes in the earlier years of this dark era, was one of the largest to date according to cemetery records.

On the front row sat many of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Lady Bird Johnson, first lady at the time, read the story of Lt. Davis’ heroic acts as well as a personal letter she had written to our family. The Citadel family, which always excels in honoring its war heroes, was strongly represented there too.

In fact, memorials to Lt. Stephen “Foggy” Davis, The Citadel Class of 1966, are in the college’s library, chapel and the barracks that house his company, Tango.

After his son’s funeral, Gen. Davis was needed back in the thick of the war in Vietnam, returning after 30 days.

But then disaster struck again. It did not take long before all of the newspapers in the country, as well as CBS national news, were putting out stories about Gen. Davis, commander of 199th Light Infantry Brigade, being ambushed and blown up by Viet Cong rocket grenades while on a search-and-destroy mission aboard a river patrol boat.

It unfolded on home TV screens “in living color” on Walter Cronkite’s “CBS Evening News.”

Gen. Davis was wounded and became the last general officer to be evacuated from the Vietnam War. He survived and became commandant at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he planted a tree just outside of the commanding general’s home, honoring the memory and sacrifice of his oldest son. The tree still stands there, with a plaque, 45 years later.

Many years past his battles, Gen. Davis joined those who had gone before him, buried alongside his oldest son with full military honors in the very same Arlington National Cemetery where he had served as a young guard. (It was later thought that the rare cancer that killed our father was, in part, due to Agent Orange, the slow silent killer of so many Vietnam War veterans).

An insightful Gen. Davis told Army Magazine once in an interview that his most moving and memorable experience during his 35 year of service to his country was “the nighttime horse-mounted inspections in Arlington National Cemetery, riding down to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.”

There is a shiny memorial plaque dedicated to Lt. Stephen Davis in the barracks that house Tango Company at The Citadel. While a freshman cadet, my son, Reid Perry Davis, had the honor of polishing his uncle’s memorial every week, as has been done by Tango cadets before and after Reid’s 1998 graduation.

The entire extended Davis family and our future generations are fortunate that journalists were there to capture the contributions made by my father and brother.

Many servicemen and women were lost in many wars, their defining moments in combat unknown but to God. The Davis father and son story is recorded for future soldiers and for all Citadel cadets.

The world knows their story of sacrifice in the true spirit of The Citadel core values of honor, duty, respect.

It is because of the memorable deeds of many duty-driven soldiers, dead and living, that we shall live to remember, on this and all Memorial Days to come.

Nathaniel Davis of Charleston, a 1969 graduate of The Citadel, wrote this for the three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren of his father, Maj. Gen. Franklin M. Davis Jr